The Field of Dreams Game – Part 1: If Major League Baseball Builds It, Clichés Will Come

- Ken Smoller

- Sep 3, 2021

- 8 min read

Updated: Apr 21, 2023

Starting a blog post with a dictionary definition from Merriam Webster‘s is a cliché in and of itself. It is a writer’s block crutch that is overused, making its presence here a paradoxical twist of the cliché concept.

Yet, both the “Field of Dreams” movie and the Field of Dreams game that took place on August 12, 2021 at the Dyersville, Iowa filming location for the 1989 Kevin Costner film both overcame their embedded cliches to capture the imagination of baseball fans and non-sports fans alike. Sometimes, cliches come into existence because they are convenient expressions of universal themes and enduring truths that cross generations and cultures. Sometimes, cliches capture a sentiment or theme so perfectly that they are excusably unavoidable. In a similar way, a touristy restaurant might transcend its “touristy” status because of uniquely special food and ambience that isn’t tarnished because of the ubiquitous souvenir tshirts.

My experience in Iowa while attending the Field of Dreams game was so fantastic on countless levels, that no cliché could have spoiled the magical event. Iowa really can be beautiful and magical. Cornfield sunsets truly are like surreal paintings that need to be witnessed in person to believe. Kevin Costner, despite accidentally swearing in the Fox telecast, remains impossibly handsome and elegant in an “aw shucks” Jimmy Stewart way. Most significantly, the game of baseball remains amazingly captivating despite all of its problems and lack of appeal to the fast paced on demand world of the smart phone era.

The “no filter needed” sunset over the Field of Dreams Ballpark in Dyersville, Iowa was so magical that it transcended any prevailing clichés.

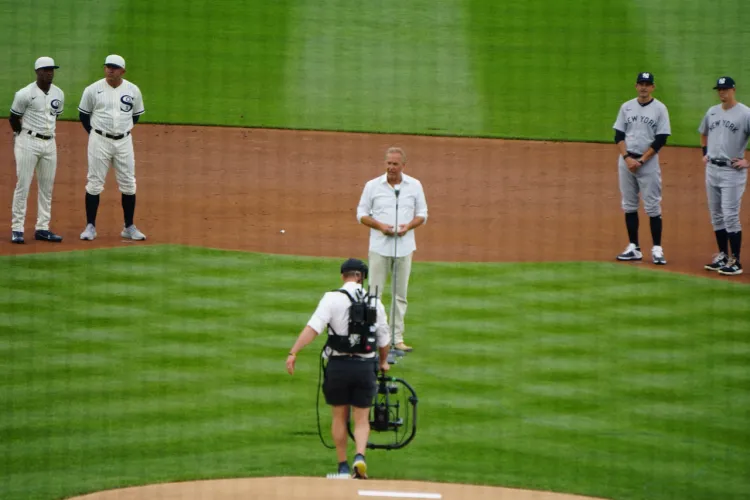

Left: The ageless Kevin Costner delivered a moving (despite being cliché-filled) speech as the White Sox and Yankees were introduced.

Right: Two “ghost player” sit atop the bleachers from at the original Field of Dreams field.

Ultimately, the film “Field of Dreams” (FOD) is a story of redemption. Dr. Moonlight Graham’s redemption comes in the form of getting his one shot at bat against big leaguers. Shoeless Joe Jackson gets the opportunity to return to the diamond one more time after his lifetime banishment for his part in throwing the 1919 World Series. Kevin Costner’s Roy Kinsella gets a chance to “have a catch” with his estranged and now departed father. The “redemption” cliché extends well beyond the film to encompass both the White Sox as a team (both in micro and macro ways) as well as to me personally. While one could easily dismiss the redemption story arc of Field of Dreams as the ultimate cliché, it is an example of one that works because the cliché truly reflects reality in a hyper loop of art imitating life and life imitating art.

Left: The sun setting over the leftfield grandstand at the Field of Dreams Ballpark.

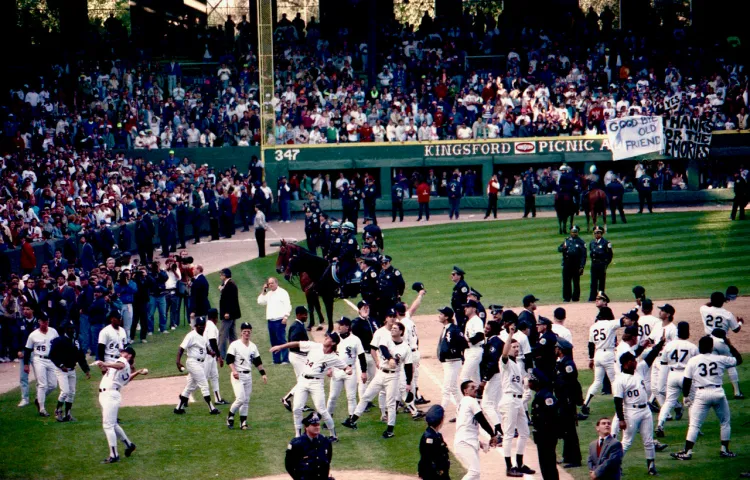

Right: The White Sox, who have enjoyed scant success since Shoeless Joe Jackson was banned from baseball, greeted fans following the final out at old Comiskey Park in 1990.

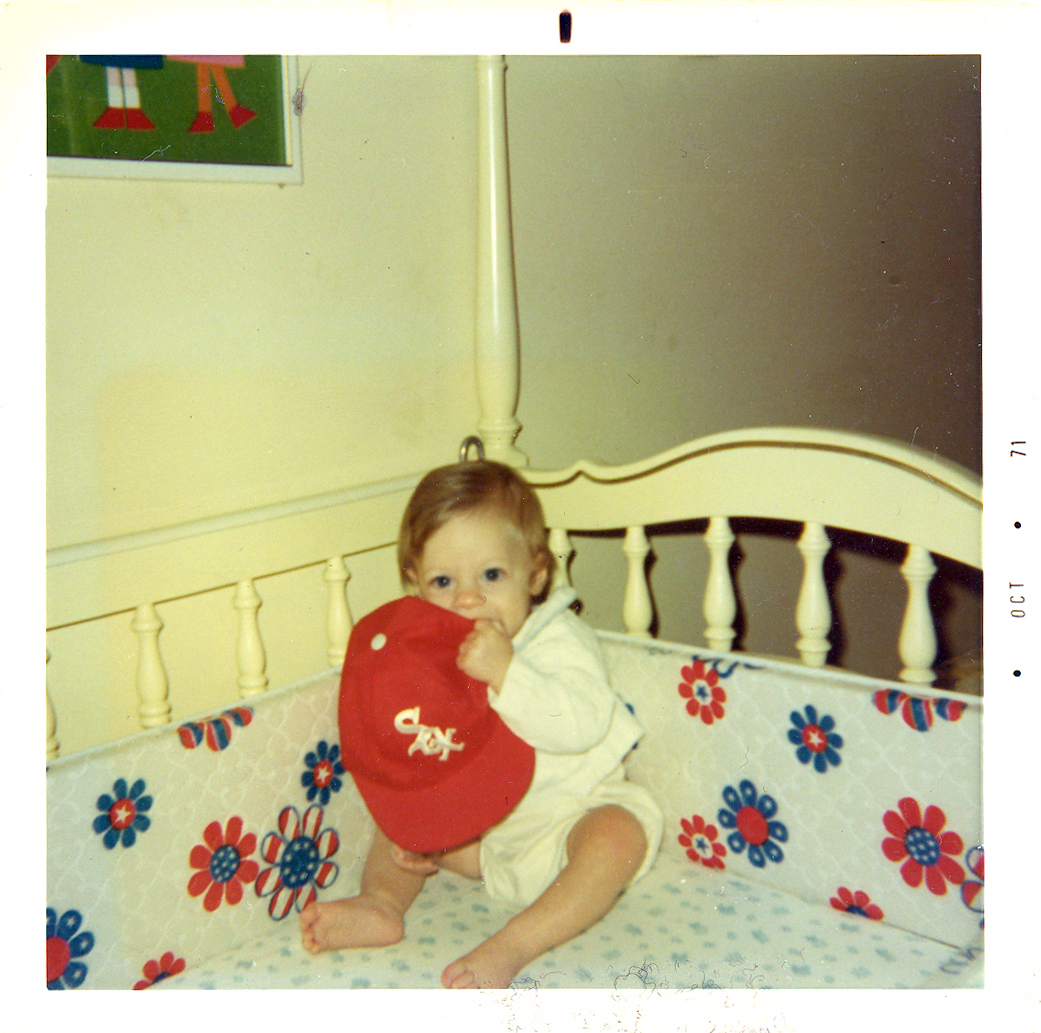

In order to understand my own slice of the redemption cliché, I need to return to 1989 when the movie was released. That summer, I graduated from Buffalo Grove High School in a northwest suburb of Chicago. Despite living deep in Cubs’ country, I always was a diehard Sox fan since my diaper days. I am told that I once cried as a child when my grandparents accidentally got me a Chicago Cubs jacket for my birthday instead of one for my favored White Sox. Like many kids, my dad’s fandom influenced mine. He also grew up in Cubs’ territory in West Rogers Park on the northern edge of Chicago, but he was a Sox fan because he fell in love with Go Go Sox era second baseman Nellie Fox in the 1950s.

My dad was so intense about his Sox loyalty, he even refused to take me to Wrigley Field (home of the Cubs from 1914 to the present) until I was a teen and the Chicago teams played an exhibition game called Crosstown Classic at Cub’s home in 1986. Instead, we would take in about 6 to 10 Sox games a year at old Comiskey Park (home of the White Sox from 1910-1990). Whether we knew it or not, we collectively identified with the “Us vs the World” persona that characterized Sox fandom.

Top: Comiskey Park, Home of the Chicago White Sox from 1910-1990

Bottom Left: Proof of my White Sox OG status in my crib in Des Plaines, IL in 1971 (Photo by Jerry Smoller)

Bottom Right: The Wrigley Field marquee before the Crosstown Classic exhibition game, the first time I was allowed to attend a game at Wrigley.

Like their crosstown rivals, the White Sox were long-suffering losers, albeit not nearly as well documented as the Cubs’ were with their cutesy “Billy Goat Curse”. The Sox last World Series appearance was in 1959 when they lost to the LA Dodgers. Until I was well into adulthood, the White Sox last World Series win was in 1917, before my grandparents had even emigrated from Eastern Europe to Chicago. That team was loaded with star players, but fate intervened in the White Sox dynasty as is famously described in the FOD film and another historically dubious book and movie of that era “Eight Men Out”.

The heavily favored White Sox threw the 1919 World Series to the Cincinnati Reds, leading to the lifetime banishment of star player Shoeless Joe Jackson and seven other key members of the team. Instead of being the dominant team of the 1920s, the Sox were gutted of their star players and a team from the Bronx filled the void. The White Sox would not win another playoff series of any kind for the subsequent eighty-eight years, while the Yankees captured 26 World Series titles in the same period.

The White Sox never won another World Series at old Comiskey Park following the Black Sox scandal. In 1991, the team moved across the street to new Comiskey Park and a wrecking ball demolished the old ballpark. Now, only a small marker is the only reminder of eight decades of baseball history on the northwest side of 35th and Shields.

Shoeless Joe’s 1919 much-disputed original sin is at the heart of the 1989 film starring Kevin Costner. Costner’s character, Ray Kinsella, had a deeply strained relationship with his father John Kinsella, who had died before the events of the film. The ultimate insult Ray leveled against his father was disparaging his father’s idolatry of the “criminal” Shoeless Joe Jackson. As part of the credulity stretching plot of FOD, Ray Kinsella turned his farm into a ballfield to lure both Shoeless Joe and his father back to some sort of baseball afterlife. The climactic redemption scene of the film is Ray and John Kinsella having a simple game of catch on the dreamy field.

The original Field of Dreams field used in the filming of the movie in 1988. The field has been a regular draw to tourists ever since the film was released in 1989.

Truth be told, I found the film to be over-the-top cheesy (skipping the corny pun for now) and I only recall watching the film once when it was released in 1989. As far as baseball films go, I always had preferred “The Natural” starring the regal Robert Redford or even Costner’s other baseball hit “Bull Durham”. In the summer of 1989, I was more concerned with graduating from high school and taking a trip that summer with my high school girlfriend for what would become my first baseball road trip to games in Cleveland, Philadelphia, New York and Boston.

Further, I was too immature and self-absorbed to appreciate the resonance of the father-son themes that flowed through the film. At the time, I barely was speaking to my own father, yet lacked the self-awareness to recognize the universality of the father/son tension present in my life. As a result of our strained relationship, we wouldn’t go to another game together for over a decade. Given all my personal life distractions, the film barely registered in my consciousness.

Top left: Municipal Stadium, Cleveland, OH (demolished 1996)

Top right: Veteran’s Stadium, Philadelphia, PA (demolished 2004)

Bottom left: Yankee Stadium, Bronx, NY (demolished 2010)

Bottom right: Fenway Park, Boston, MA in 1989 before major renovations.

When Field of Dreams was released on April 21, 1989, I was busy planning for a baseball road trip from Chicago to Boston. Only Fenway Park is still standing today

Despite not revering the Field of Dreams film, I felt drawn to the Field of Dreams game once Major League Baseball announced the event in August 2019. I saw on twitter that MLB had planned on converting part of the actual movie site into an major league ballpark for a White Sox-Yankees game scheduled for August 13, 2020.

As the press release described, the ballpark’s dimensions would be patterned after the now-demolished Comiskey Park, which had housed the White Sox for 80 years. That fact likely put me over the top and I immediately reserved a hotel room about 20 miles from Dyersville, Iowa and created a Google News alert to monitor all media tidbits about the game and ticket sale. Throughout the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020, I closely monitored developments regarding the game. First, MLB announced the St. Louis Cardinals would replace the Yankees, then they announced the game would be fanless, then the game was postponed indefinitely.

The outfield dimensions at the Field of Dreams ballpark were subtantially based on the dimensions at old Comiskey Park, pictured here in its final season of 1990.

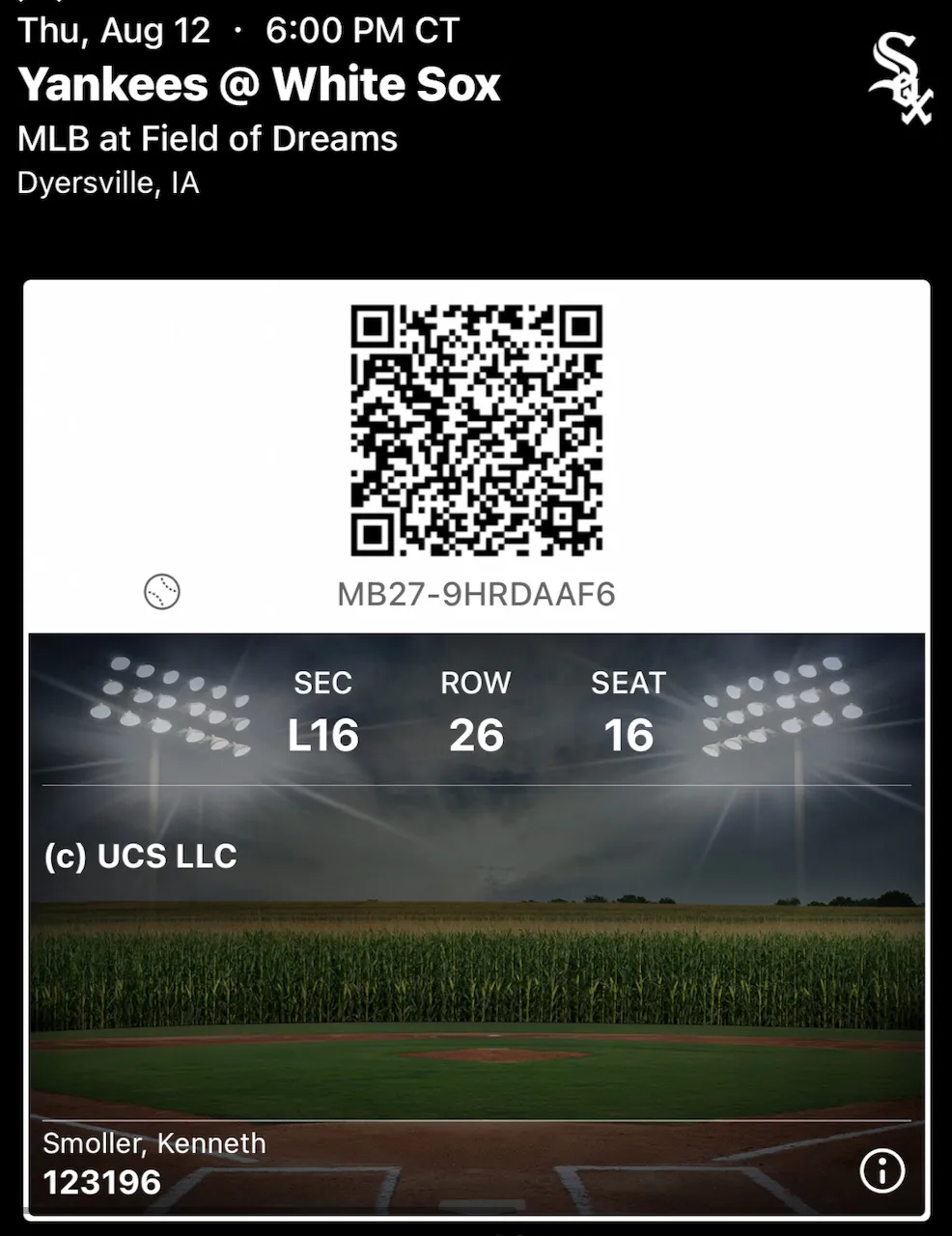

Once the Covid vaccines made resuscitating the game a reality in the Spring of 2021, I turned my attention again to Iowa and my hopes for securing a ticket. Needless to say, the ticket would be a hot commodity given that no major league game had ever transpired in Iowa and the stadium would be limited to approximately 8,000 fans. I was disappointed when the League announced that only Iowa residents would qualify for tickets and figured there was no way to get a ticket at any cost. Later, tickets were released to season ticket holders of both teams and I was lucky enough to find a single ticket at a semi-reasonable price on Stubhub. I was ready to make my reverse Ray Kinsella cliché driven journey from Boston to Iowa.

Once tickets were doled out via various lotteries, baseball fans from New York and Chicago snatched up many of the tickets on the secondary market.

Cliché alert!!!! In a key moment of the film, James Earl Jones speaks the line “they’ll come to Iowa for reasons they can’t even fathom.” This film quote absolutely applied to me as I personally was unsure why I even wanted to go to through the expense and hassle of traveling to Iowa during the dog days of August. My primary desire to go related to my deeply eccentric and quixotic obsession with photographing stadiums, in particular, ballparks.

Dating back to before I picked up my first camera, I always loved the unique design of each ballpark. When I was a kid, I used to fashion blanket forts into ballparks or sketch my favorite parks. As I got older and started to take photography more seriously, I started a never-ending scavenger hunt to photograph ballparks and stadiums throughout the United States and beyond. I have since photographed over 2,000 stadiums, including over 500 ballparks in the United States, Canada, Europe and Japan.

While sometimes I have photographed empty stadiums on off days, I have attended major league baseball games at 52 current, former or temporary ballparks including Expos games in San Juan, Puerto Rico; Blue Jays “home” games in Dunedin, FL and Buffalo, NY; and the London Series between the Red Sox and Yankees in London, England. Given my lifelong obsessive ballpark hopping, I felt utterly compelled to witness a White Sox game in this most unusual of ballparks despite my relative indifference to the 1989 baseball cinematic fantasy. If nothing else, I knew the photographs would be surreally cool and the site would be uniquely memorable.

All photos and text by Ken Smoller (aka Stadium Vagabond) unless otherwise noted above. Copyright 2023

A drawing that I drew of old Comiskey Park when I was a kid, which was loosly based on cartoons drawn by legendary sketch artist Amadee Wohlschlaeger.

Comentários